International trade shapes the destinies of nations, weaving together markets and cultures in a complex tapestry of exchange. Whether a country runs a surplus or deficit influences jobs, industries, and even geopolitical relationships. By grasping the underlying forces and recent data, we empower policymakers, business leaders, and citizens to make informed decisions.

In the following sections, we explore core definitions, analyze 2025 trends, uncover the mechanics of global trade, and propose strategies that foster sustainable growth strategies and long-term competitiveness.

A trade deficit occurs when a nation’s imports exceed its exports over a given period, resulting in a negative balance of trade. Conversely, a trade surplus arises when exports outweigh imports, yielding a positive balance. These imbalances may apply to goods, services, or their combined value.

The broader framework is the Balance of Payments, which records all economic transactions between residents and non-residents. It splits into two main accounts: the current account (trade in goods and services) and the capital and financial account (cross-border investments and loans).

The United States trade deficit widened significantly in May 2025, as imports and exports moved in opposite directions. Exports fell while imports remained stubbornly high, driven by anticipation of upcoming tariffs.

The six-month moving average stands near –$103.2 billion, reflecting persistent imbalances. Globally, G20 merchandise exports rose 2.0% in Q1 2025 while imports climbed 3.1%, highlighting uneven recovery across regions.

The current account measures cross-border flows of goods and services. A surplus indicates net export strength; a deficit suggests robust import demand or structural weaknesses. The capital and financial account captures investments—direct, portfolio, and other financial assets—indicating how deficits are financed.

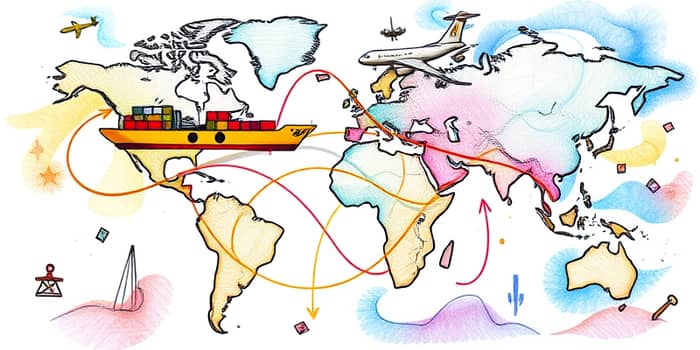

When a country imports more than it exports, it must attract capital inflows to balance payments. These inflows can come as foreign investments in government bonds, equities, or real estate, providing the funds to pay for excess imports.

Persistent deficits can strain domestic industries and raise concerns over job losses in manufacturing sectors. Yet, a deficit may also reflect strong consumer demand and dynamic investment, signaling confidence in an economy’s prospects.

Surpluses bolster domestic producers and can finance international investments. Countries with consistent surpluses, such as Germany or China, accumulate reserves and wield significant influence in global financial markets.

National security considerations arise when essential goods—like semiconductors or medical supplies—are predominantly imported. Governments must balance open markets with strategic resilience to safeguard critical supply chains.

In early 2025, the U.S. trade gap narrowed with China, Switzerland, and Canada but widened with the EU, Mexico, and Vietnam. Key export drivers included aircraft, passenger vehicles, and non-monetary gold, while imports surged in cell phones, pharmaceuticals, and computers.

The monthly volatility—averaging an 8.8% absolute change—demonstrates how sensitive trade balances are to seasonal cycles, policy announcements, and global disruptions.

Trade deficits and surpluses are not inherently good or bad; they reflect deeper economic dynamics that require nuanced interpretation. By combining rigorous data analysis with strategic policy and private-sector innovation, nations can harness trade flows to drive growth, resilience, and shared prosperity.

Understanding these forces enables stakeholders—from government officials to small business owners—to craft strategic economic planning and build robust financial inflows that support a brighter, more interconnected future.

References